A genealogical essay I wrote that discusses the transition and evolution of the ‘save game’, both in hardware and software, and the surrounding culture that developed with it.

Estelle Tigani

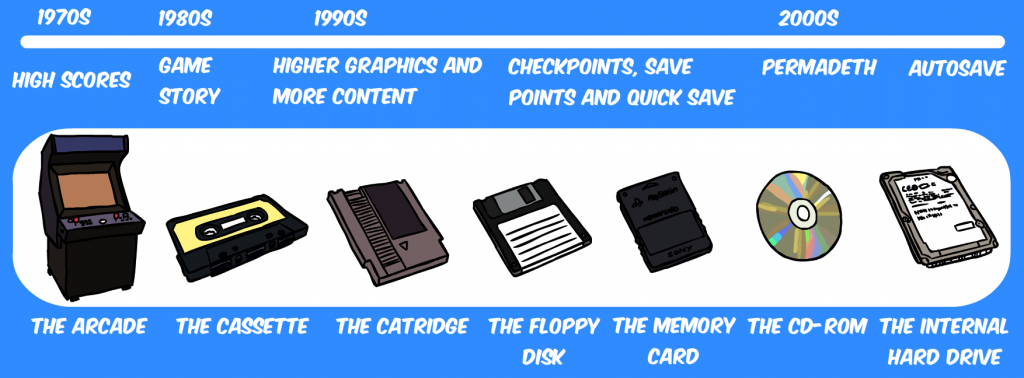

Throughout the development of video games over the centuries, the ‘save game’ has become an element that has naturally formed alongside gameplay itself. As games sought to become more lengthy and complex, whilst its platforms have advanced in technology, the save game has turned into a downright necessity. Originally implemented as a means of saving one’s personal statistics, it then went on to become a background ‘autosave’ that allows the player more time to spend enjoying the enthralling experience.

The save has developed along with technology; they are hand-in-hand. The first games to grace the eyes and hands of players never had saves purely for the fact that gameplay itself was still theorising its way into the ‘industry’. There’s a good chance that Thomas T. Goldsmith Jr. and Estle Ray Mann, the creators behind Cathode-Ray Tube Amusement Device never even considered save. And this should come as no surprise. Previously, the only games known to man were one-shot matches of tennis or football that generally lasted until there was a winner, before ending. Even the majority of schoolyard games would end when the children were called back in, only to start all over the next day. Even if these minimal-mechanic games wanted to retain progression, the technology available was far from catching up. Some of the earliest home computers barely had storage, which to many at the time was still a thing of beauty – a laughable dream.

It was the early age of the arcades that saw the first glimpse of the saves, in the form of ‘high scores’. Despite the fact that arcade games were still one-shot play throughs, the whole experience from these games came from how far a player could advance and/or stay alive in the game before game over. The original Space Invaders thus introduced the ‘high score’ and the culture around saving players’ statistics was born. Dedicated Space Invaders fans became incredibly talented hardcore players. As a new element for games, the save did not provide players with an option to ‘quit and come back later’, but rather to hang their trophy scores on the wall for all to see because they could not. The saving of high scores developed a community of striving hardcore players who spent hard-earned coins to see their glorious number at the top of that list.

By the 1980s, a new element of the game was born as a result of the freedom the save game provided. This element was the game story. Arcades first cautiously drifted into this area and managed to create a story around their more technically-inclined mechanics, but they were indeed minimal (consider the Jump Man and Pac-Man games, for example). However with the release of The Legend of Zelda and Zork, among others, games created a structured story and setting for their gameplay, and with that, a genre. Finally, the industry had tools to work with in order to create experiences that could identify themselves as their own entity. Brands such as Mario bursted onto the television screen, and with that, a new culture that went beyond mere high scores. Now it was about what event or segment the player was up to, or which ‘boss’ they had to fight. All real because the save game offered the player the opportunity to play over a period of time, which was longer than just an hour or two. It could be said that the save game almost invented the game story, but in turn, the save game became a necessity because of the game story. Initially, some games offered home PCs with ‘passwords’, or a set of characters which the player could write down and type in to resume at a later date. This then developed into cassetes and floppy disks; home PCs could now produce lengthy stories and the text adventures, which grew consequently, allowed games to be taken seriously as a form of literature. Consoles stored their save data on the cartridges they sold their games in, using battery-charged RAM, allowing friends to take their own saves to each other’s houses for a communal experience.

The 90s opened with promise as new consoles allowed for more space to be saved on new technology. Not only could the player save more games to their console, but developers could produce more content and with the higher 3D graphics that were also rising. Likewise, home computers were become vastly more cheaper for the household whilst also becoming more powerful and efficient, allowing far more storage than could be dreamed of ten years before, both internally and with the extraordinary release of the CD-ROM. The save acted almost as an unquestionable requirement for any game, and the larger amount of space available and higher quality of graphics made the industry highly competitive. Players now needed to save as games required far more time to complete. The average video game during the 90s exceeded beyond 7 hours of gameplay, according to HowLongToBeat.com, with Duke Nukem 3D reported with an average of 8 hours and 40 minutes, whilst the popular Final Fantasy VII forced players into a crazy 60 hours and 32 minutes.

Generally speaking, three ways of implementing the save game was used; players were required to pause and open the game’s menu to save, players were given the option to save after a specific even or completion of a task, or players were forced to scout out specific areas known as save points. The save point is the most interesting, because it absolutely changed the way players played the game; how often they visited and utilised the save point (assuming they could visit it more than once), how important the finding of save points were within the overall gameplay experience (generally depending on difficulty of game) and how players planned their resources around the timing of save points. Whole strategies have been developed around save points. In turn, developers had the chance to manipulate gameplay or difficulty depending on their specific positioning of save points. Final Fantasy VII was a perfect example of such manipulation. Checkpoints were also used, but more so to do with respawning (i.e. saving internally within the game, which would not actually be hard coded into the system permanently, therefore the player could not return to that point when the game was reloaded). Save points and checkpoints were commonly adapted into games and used as a mechanic to the game itself; for example, Resident Evil save points were represented as typewriters and required the player to obtain an ink ribbon item in order to use them. One save point in Chrono Trigger would actually attack the player if they attempted to use it. Other games have forced the player to spend currency to use a save point, or sacrifice something of importance, and others have used journal entries the character made at save points for plot developments later on. In Metal Gear Solid, characters in the game actually commented on how often the player saves. Games have also been known to pass saves on to sequels.

As a result of the intense strategies surrounding save points in order to avoid player death, as well as the ‘quick save’ option implemented in many PC games, which allowed players to save any time they wanted (given the circumstances) with a simple keystroke, a sub-set community of hardcore players arose, who chose to play specifically in ‘permadeth’(permanent-death), or rather, a hardcore mode where the game would only offer one life and no respawn, meaning death would reset the game to the start with all levels and abilities set to zero. When the game did not offer such a mode, players of the Permadeth community would manually turn the game off and restart. This type of rebellion against the save game created many forums, whereby members would share and compare their stats, which was usually how far they managed to stay alive in the game before dying. Not only was this a flawless reflection of the attitude towards high scores in the arcade games of the 80s, but this proud community would also publicly voice their loathing towards players who used quick save excessively, labelling them ‘cheaters’. An example of a game which produced such a community from its hardcore permadeth mode was Diablo II. Permadeth players of Diablo II even went as far as to create ‘The Hardcore Graveyard’ – a place where they could record their dead character’s stats, or ‘deed’s.

The previous notion of ‘portable saves’ that were invented along with the cartridge and the floppy disk now evolved into Sony’s Memory Card for the Playstation. With the popularity of video games, Sony assumed friends would own the same titles, and therefore created the memory card as a means of transporting only save data, rather than the whole game. This incredibly versatile system meant that Sony also did not need to stress over the capacity of its consoles, when players were able to purchase more Memory Cards for more storage. More than one child at home could also own their own individual Memory Card with their own saves and statistics stored safely without prying siblings or friends.

The save game continued to evolve with the release of Pokemon, which allowed players to collect ‘pocket monsters’ and trade them with friends. The concept sought to use the save game itself as an actual mechanic, whereby the player’s statistics and collection of monsters could be channelled using a link cable to others. Pokemon’s creator, Satoshi Tajiri – a lover of insects as a child – envisioned creatures moving back and forth across the cable.This connotative concept is one of many examples aiding David Myer’s theory of semiotics in video games, seen in The Nature of Computer Games: Play as Semiosis. The use of a cable on the Game Boy meant that the console could send save data to others without the use of an external storage unit like the Memory Card. For the first real time, the save game became the dominating mechanic of a video game.

Technology always did play a huge role in what the save game was limited to, however the start of the 21st century advanced computers and their storage capacities so far forward that graphics did indeed shake hands with the ‘uncanny valley’, and consoles such as the Wii, the Playstation 3 and the Xbox 360 introduced the internal hardrive. Yes, the era of the portable Memory Card or the cartridge or the floppy disk did see its end, but what these new consoles offered was a storage capacity that was so large, the 60 gigabyte Playstation 3 was estimated to hold around 202,000 game save files.

These new high-powered consoles established a new level of creativity amongst developers, who started to seriously think about ‘the experience’ as a mechanic itself. Innovative ways to draw a player into an experience then required another development of the save game; namely autosave. The necessity to keep the player immersed in an experience meant interface mechanics such as the heads-up display and the save game were minimalised dramatically or even removed. The autosave replaces the checkpoint that was common in the 90s, and means that players do not have to remove themselves from the game experience for a few seconds to go out of their way to save. Rather, the console will do it in the background for them, and should they chose to return at a later stage, the game usually picks up exactly where the player left off, or very close to (this indefinitely removes the need for save points). The manipulation of difficulty using save points in games is now generally removed, because players can ‘inch’ their way through a game using autosave. Thus it allows gamers of any skill level to play, with the average skill level being far lower than gamers that played arcade games 20 years before. As a result, the last decade has seen an increase in ‘lazier’ gamers and a higher introduction of new players – or ‘noobs’ – to the market (something which enrages many hardcore players). This should not be surprising, however, as many developers are aiming to target their games to a larger market (i.e. the recent ‘casual’ games). The Kinect on the Xbox 360 requires the autosave for the pure reason that players are no longer using controllers, and will not have the time to stop their physical activity to save their progress (it should also be worth noting that initial Kinect games like Kinect Adventures were based around original arcade-style one-shot plays with high scores). Similarly, games on iOS utilise autosave so that players do not have to go out of their way to save when they are on the go, and pressing the Home Button on the iOS device to look at something else generally saves the game automatically for the player’s benefit.

The save game has seen a repeat in culture today that was established around it before. Interestingly, recent MMO’s such as World of Warcraft utilise autosaves for a reason other than story or experience; players on WoW admit that it is their character (or specifically, their WoW profile) – which they have worked on so hard to upgrade in such a long time – that they wish to save. If the game forced them to start over the story, the anger of the players would be laughable compared to if the game forced them to create a new player from scratch every time they loaded. This is a trend that almost reflects the high scores of the arcades; the players see their personalised characters as ‘trophies’ (emphasised, of course, by the fact that players can purchase each other’s accounts, which also reflects how many coins were sacrificed to arcade machines for high scores). The Nintendo 3DS has once again used save data as an actual mechanic like its ancestor, the Game Boy, for Pokemon years before. The social Street Pass allows players to create a customised avatar, which can play games and collect information, and which can then be traded with others wirelessly. The dominating fun of this save mechanic is collecting others’ avatars and keeping them in the Street Pass central hub, thus using a collection of save data as a trophy itself.

The great Permadeth communities of extreme hardcore players still continues on in the 21st century. The Armed Assault 2 mod DayZ shined a light on this community once more, with players choosing to spend hours immersing themselves in what mimicked very closely with a realistic zombie apocalypse; limited supplies, one life. An article written by Steve Fulton entitled ‘The Rise of the Hardcore’ mentions that it is the developer’s attention to creating a believable ‘experience’ that has seen players turn to DayZ, and other genres such as Permadeth, because it creates fear. The real fear of zombies, with real death, and no saving of life. Another game that uses this concept well is Dark Souls. Also, just as with the older Permadeth culture of the late 90s, hardcore gamers continue to fire hatred right in the direction of those who, in their eyes, have ‘cheated’ by making the game easier for themselves. A good example of this surrounded the controversy of players loading other people’s save files to gain a higher Gamerscore on Xbox Live, resulting in a response by Microsoft themselves and a permanent branding of ‘cheater’ on such profiles.

If players are now turning to experiences that seem more realistic and more immersive, then the games industry might have to consider where the save game plays a role in that. It is worth pondering whether the save game still removes players from a true experience, because it offers a sense of immortality on their heroic characters. Would the Call of Duty franchise – which has received ongoing scrutiny for desensitising teenagers’ attitudes to warfare – become more ‘realistic’ if it introduced permadeth? Perhaps, the industry will once again turn to an age where saves are not an option for games, but rather, weakened characters in combat and permadeth might ring true to these cries for experience. Sqaure Enix’s Tomb Raider proves this with their new redesign of a ‘realistic’ Lara Croft, who weakens at the hit of a bullet in gameplay. Or are games meant to be just that; games? In which case, the save game and the sense of immortality that comes with it should be retained so that games can be purely made for light-hearted fun?

References

D.S. Cohen. “Cathode-Ray Tube Amusement Device – The First Electronic Game”. About.com. [http://classicgames.about.com/od/classicvideogames101/p/CathodeDevice.htm]

Geddes, Ryan; Hatfield Daemon (2007-12-10). “IGN’s Top Most Influential Games”. IGN. [http://au.ign.com/articles/2007/12/11/igns-top-10-most-influential-games]

“Final Fantasy VII”. HowLongToBeat.com. [http://howlongtobeat.com/gamebreakdown.php?gameid=276]

Moran, Chuck; (2010). “Playing with Game Time”. Fibrecultre 16. [http://sixteen.fibreculturejournal.org/playing-with-game-time-auto-saves-and-undoing-despite-the-magic-circle/]

Royce, Brianna; (2012-01-9). “The Daily Grind: Do You Play in Self-Enforced Hardcore Mode?”. Joystiq. [http://massively.joystiq.com/2012/01/09/the-daily-grind-do-you-play-in-self-enforced-hardcore-mode/]

Glater, Jonathan D.; (2004-03-04). “50 First Deaths: A Chance to Play (and Play) Again”. New York Times. [http://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/04/technology/circuits/04dead.html?ex=1394341200&en=665cc565e0388432&ei=5007&partner=USERLAND]

‘Drannog’. “A Case for a Permadeth Server”. IGN. [http://wowvault.ign.com/View.php?view=Editorials.Detail&id=4]

Swider, Matt; (2007-03-22). “The Pokemon Series Pokedex”. Gaming Target. [http://www.gamingtarget.com/article.php?artid=6531]

Myers, David; (2003-05-28). “The Nature of Computer Games: Play as Semiosis.” Peter Lang AG.

‘Acta_non_verba’; (2008-11-01). “Playstation 3 General Discussion – The “Hard Drive Information” Thread”. Playstation Forum. [http://community.eu.playstation.com/t5/PlayStation-3-General-Discussion/The-quot-Hard-Drive-Information-quot-Thread/m-p/5800225#M1072707]

Jimenez, Christina; (2007-09-24). “The High Cost of Playing Warcraft”. BBC. [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/7007026.stm]

Grant, Christopher; (2008-03-25). “Cheaters Branded on Xbox Live, Gamerscores Reset”. Joystick. [http://www.joystiq.com/2008/03/25/cheaters-branded-on-xbox-live-gamerscore-reset]

Fulton, Steve; (2012-07-30). “The Rise of the Hardcore”. Gaming Daily. [http://www.gamingdaily.co.uk/2012/the-rise-of-the-hardcore/]

Thang, Jimmy; (2012-02-23). “What Do Real Soldiers Think of Shooting Games?”. IGN. [http://au.ign.com/articles/2012/02/23/what-do-real-soldiers-think-of-shooting-games]

Recent Comments